Andrew Wyeth was an American painter born in 1917 in the small rural Pennsylvania town of Chadds Ford. The youngest of five children, born to an illustrator and artist father, N. C. Wyeth, Andrew Wyeth’s childhood was shaped by his ill health. Stricken with whooping cough at a young age, his parents opted to pull him out of school and provide for his education at home. He was home schooled in many subjects, including art education. He died in January of 2009, at the age of 91, leaving behind several children, one of whom is now an exhibiting artist as well.

Andrew Wyeth was an American painter born in 1917 in the small rural Pennsylvania town of Chadds Ford. The youngest of five children, born to an illustrator and artist father, N. C. Wyeth, Andrew Wyeth’s childhood was shaped by his ill health. Stricken with whooping cough at a young age, his parents opted to pull him out of school and provide for his education at home. He was home schooled in many subjects, including art education. He died in January of 2009, at the age of 91, leaving behind several children, one of whom is now an exhibiting artist as well.

No study of Andrew Wyeth would be complete without addressing on some level his popularity. Known as a “painter of the people” Andrew Wyeth achieved a level of artistic success few artists even dream about hitting. Almost as his stardom increased, so too claim the critics, did his reputation as an artist decline. It’s been said that his stardom “cannibalized” his art-inexpensive prints saturated the market to the point of lowering the value of his “real” work. A student of art today could almost undertake a complete study of Wyeth, not just as an artist, but perhaps as a lesson in “how to move art to the masses” (maybe even “how not to move art to the masses” depending upon your point of view.) Much has been written about Wyeth, both during his heyday as a best selling artist and in his later years but, popularity and commercial success aside, Wyeth was an influential painter.

Known to shun traditional oils, Wyeth instead opted to work with watercolors, drybrush (a technique where watercolors are used but water is squeezed or otherwise removed from the brush) and egg tempera (a medium where egg yolks are used as a binding agent and mixed with pigment to make paint.) Perhaps Andrew Wyeth is famous not so much for the type of painter he was, but more the painter he wasn’t, as his subjects and style also varied drastically from many of the abstract oil painters from that period.

Andrew Wyeth painted typically rural subjects, like those you might find in rural Pennsylvania. His subjects were often open, desolate landscapes and much of his work showed traces where humans were left behind (tracks, roads, beds, chairs, etc.) Wyeth preferred the quiet contemplative desolation of the rural landscape-much of his work sets a quiet mood. He liked to disguise the familiar by light or distance and there’s a certain “approach yet withdrawal” about his work. Standing in sharp contrast of the abstract painters that were popular of the day, Wyeth painted a quiet realism-his work is as much about detail as it is about space, a study in both the pensive and the perspective of rural American life at the time.

What Photographers Can Learn From Him

The concept of a “quiet mood” is a wonderful “take” for a photographer looking to Wyeth for inspiration. Since Wyeth was not an abstract painter, his work bears the mark of realism-as a photographer, here is an example of heavily used textures with a clear focus. So much of today’s “textures with layers” work really resembles Wyeth’s paintings. His work was subtle yet detailed-photographers should be comfortable with a certain level of detail, as much of photography is about detail and it has roots in the same sort of realism that Wyeth knew, yet a photographer could learn a lot by incorporating a certain subtlety into their work, the way Wyeth did.

Much like Michael Kenna, a Wyeth painting is more a dialogue with the viewer than it is a finished product. The concept of suggestion-the traces of human touch left behind can really add a lot to photographic work. A lot of photographers (myself included) don’t always work with portraits but, by leaving out a person, a photograph can suffer-the photographer can drop a center of interest that’s naturally present with a portrait. By opting to include instead hints of a person, small touches, subtle tells of a presence that have been left behind-things like chairs, beds, boots, signs, even tracks in the earth-Wyeth’s work become more like a haiku and less like prose-subtle, contemplative, pensive, moody. These elements can translate directly, as they do with Kenna, to photography and the notion of a creating a discourse with a viewer, rather than crafting a finished product lends itself well with the modern notion of highly interactive art. It’s as if the viewer is drawn in by what’s not present in the image and that sort of “approach yet withdrawal” creates a natural tension in the work.

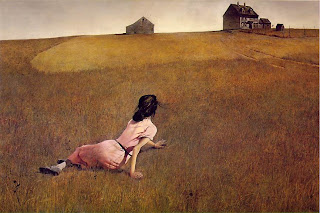

Wyeth’s color palette was simple, featuring many browns and grays, and he used light and distance well in his work to give depth and assign meaning. To paraphrase that old adage, “objects closer in mirror are more important than they appear” would sum up Wyeth’s perspective quite well.  In his famous piece, Christina’s World, Wyeth painted a girl, crippled by polio, crawling across an open field with a house in the distance. The use of space, sense of depth, and level of detail in the work lends meaning and importance to the elements in the painting. Once again, photographers could learn a lot by looking to Wyeth’s example of using light or distance to assign importance to elements in an image. By putting more important objects in the front of the frame, adding a lot of depth, working with space, detail, subtle colors, and texture carefully, a photographer could really craft images with great impact.

In his famous piece, Christina’s World, Wyeth painted a girl, crippled by polio, crawling across an open field with a house in the distance. The use of space, sense of depth, and level of detail in the work lends meaning and importance to the elements in the painting. Once again, photographers could learn a lot by looking to Wyeth’s example of using light or distance to assign importance to elements in an image. By putting more important objects in the front of the frame, adding a lot of depth, working with space, detail, subtle colors, and texture carefully, a photographer could really craft images with great impact.

For his quiet mood, his mastery of light and distance, his texture with focus, the quiet desolation of Andrew Wyeth earns him a spot in the ranks of “Painters Every Photographer Should Know.” You can read more about Andrew Wyeth on the wikipedia entry about him and look for more posts (and painters) as part of the series.

—————————————————————————————————————

This is next in a series called “Painters Every Photographer Should Know.” The painting shown here is Andrew Wyeth’s Master Bedroom 1965. Please note that the paintings in this series are not copyright the author of this website, may be subject to international copyright law, and are provided her for educational purposes only.